I’ve written quite a bit about our filmmaking process at the SNL Film Unit so I thought I would change it up and write a post about another side of my professional life: documentary filmmaking. The timelines of docs and SNL couldn’t be further apart: our SNL spots are produced in sometimes less than 24 hours; my documentary “Bigger Stronger Faster” took over 3 years, including 20 straight months of editing. They are inherently different filmmaking formats, but sometimes those formats overlap…sometimes we shoot our SNL spots with documentary aesthetics and sometimes my documentary work is informed by my years of shooting recreations at SNL.

The final two SNL spots of 2014 — both directed by Rhys Thomas — were “doc style” spots. First, for Martin Freeman’s show, we made a mash-up of “The Hobbit” and “The Office” (the British version, naturally), imagining a world where Bilbo Baggins returns from the Battle of Five Armies only to take a job at a paper mill.

The following week — the final show of the year — we paid homage to our collective love of Sarah Koenig’s “Serial” podcast with a Christmas sequel, digging into the suspicious story about an elf named Kris Kringle. For fans of the podcast, this script by “Serial” super-fans Cecily Strong and Bryan Tucker was a real treat.

The making of both SNL spots had a lot of similarities to a new documentary that I’ve been making for the past year – a story about immigration and deportation set in New Orleans. I don’t have a title for the documentary yet so let’s just call it “the doc”.

Some people would say that the only true “documentary” is cinéma vérité – a style that focuses on capturing events spontaneously, usually without voice over, interviews or recreations. Films like “Grey Gardens”, “Salesman” and “Gimme Shelter” are all great examples of cinéma vérité – all three of those films made by the Maysles Brothers, who were pioneers of the style.

But of course there are a lot more documentary styles than just vérité. Documentaries like “Man on Wire” by James Marsh, “Standard Operating Procedure” by Errol Morris and “The Imposter” by Bart Layton are blurring the lines between documentaries and traditional cinematic features. As Michael Moore put it, “People don’t want to be lectured, they want to be entertained….Don’t make a documentary, make a movie!”

Even as the documentary form leans toward cinema, “doc style” has become a part of the mainstream fictional vernacular, particularly for comedy. Mockumentaries like “This is Spinal Tap” and “Waiting for Guffman” have inspired a wave of doc-style comedies, including some the most successful shows on TV, like “The Office“, “Parks & Recreation” and “Modern Family“.

This blend of fiction and nonfiction is definitely guiding my new documentary. My approach to documentaries has been to take the techniques and skills that I’ve learned from making fictional features and TV for the past fifteen years and apply them to nonfiction stories.

For example, the lighting of interviews for “Hobbit Office”, “Serial Christmas” and my new doc are all very similar. I like to keep doc-style lighting very simple – using only one source if possible, along with a frame of diffusion to soften the source and create a more natural look.

For the SNL spots, I was using a Kino Flo Celeb 400Q – a new LED from Kino Flo. I love this light! It’s roughly 2’x2’ (30” x 26”), with the output of a 1K tungsten soft light at about a quarter of the power. It has dial-in color temperature from 2700˚ to 5500˚ and a CRI of 95 – meaning that it’s very clean, with none of the green/magenta shifts that you sometimes find in older (or cheaper) LED lights. It’s powerful, lightweight and very shallow.

For the doc, I’m taking the same single-source approach, using a 4’ 4-bank Kino Flo fluorescent light. It produces about the same amount of light as the Celeb 400Q but doesn’t have the adjustable color temp. IMO, the Celeb is a better light for this application, but in fairness, it’s also a bit pricier. Even though our budgets at SNL are pretty modest, my doc is a fraction of those budgets, and a 4-bank Kino is a great option on a tighter budget. I should point out that the newest Arri T1 tungsten fresnel is an excellent, comparable light and is half the price of a Kino Flo. The downsides are that it’s tungsten-only (no daylight option) and it takes about 4-times more power. For me, a light that can easily be daylight or tungsten and is never going to pop a circuit is sometimes worth the extra money — even on a doc budget.

For most interview lighting setups, I like to add diffusion – usually a Full Grid – as large as I can manage in the space. For the SNL spots I used a 6’x6’ frame. On my doc, I’m using an 8’x8’ frame. With that very basic soft key light, I actually spend most of my energy controlling contrast. Lack of contrast is the biggest culprit of bland lighting that I see in so many documentaries, corporate videos and other “interview” setups. So often you’ll find yourself shooting an interview in an off-white office or living room with off-white furniture – and no surprise: the interview looks flat and boring!

The fundamental tool to create the contrast that your interview may be lacking is “negative fill” – the opposite of a fill light. It’s basically just a simple black wall. That could be a 4’x’4 Solid (or larger solid), it could be a roll of duvateen cloth, it could be a sheet of black foam core that you bought from Staples…it could even be a black bed sheet. The point is to control the light bouncing off the walls or spilling in from skylight.

Of course, sometimes your setups may already be too contrasty. Maybe you’re shooting in a dark room and the shadows on your subject’s face are too dark for the tone you’re trying to create. In that case I would reverse the black to a white bounce source — my favorite soft bounce is a Bleached Muslin.

All of the interviews in the SNL spots and my doc use this same combination: single light source, Full Grid diffusion and contrast control: either negative or positive fill. Another similarity is that all of the lighting is planned in advance. I like to use Adobe Illustrator to create overhead diagrams of all my shoots. Even when the setup is as simple as one of these interviews, I still rely on Illustrator to pre-visualize the setup. This routine helps me work faster, but even more importantly, it helps me avoid pitfalls on the shoot day. By plotting the setup, I can discover in advance that the room is too small for the setup I was planning, or maybe there’s a smart way to use a window as the light source instead of a light – which would be faster and usually more natural-looking.

We shot both SNL spots with the same camera package: the new Arri Amira with a Fujinon Cabrio 19-90mm lens, which has an ENG-style rocker zoom control. For “Hobbit Office”, to recreate the signature style of “The Office”, the camera was shoulder-mounted with no focus-puller. We wanted to see the operators finding focus and zooming mid-shot.

On the other hand, we thought the look of “Serial” should be a little slicker so my 1st AC (Paul Schilens) had a wireless follow focus attached to the lens and he kept the shots sharp without the feeling of an operator finding focus. For both spots, I added ½ Tiffen Black Diffusion because I find the Cabrio lens to be a little too sharp. Too much sharpness screams “video” to me and we were going for something more filmic in both spots. The “Serial” spot also featured archival footage which we shot with a 5DmIII and believe or not — an iPhone in the hands of our director, Rhys — and treated to look like dated photographs and old home videos.

My camera setup on the doc is a little different: I’m shooting with a Canon C500 and a Canon 30-105mm cine-zoom with no filters. I’m also shooting 4K resolution – a departure from these two SNL spots, which were both shot at 2K resolution – the highest resolution available on the Amira (note: Arri announced a 4K upgrade to the Amira but the upgrade was not available yet at the time of our shoots).

Which brings me to the big resolution debate: when and why do you really need to shoot 4K? Here’s my take on this debate:

There are two primary reasons to shoot 4K and they are mutually exclusive:

1) The Future Proofing Argument

2) The Extraction Argument

The Future Proofing Argument is a good argument for some projects: someday soon, 4K distribution will be upon us; if you shot your project in 4K, it can be distributed without needing to be up-rez’ed from 2K or 1080. That means that your project will look better on that 4K television and it may mean that the project is worth more to the distributor/network (but not necessarily). The SNL Film Unit is a great example of a scenario where future-proofing makes sense: our spots will be repackaged into future SNL clip shows to be broadcast in 4K and sold as 4K Blurays, a la “Best of SNL Film Unit”. Having said that, there is no mandate from anyone that we shoot in 4K; it just seems like a good idea and we’ve shot most of our spots this season on the Red Epic Dragon at 4K or 5K.

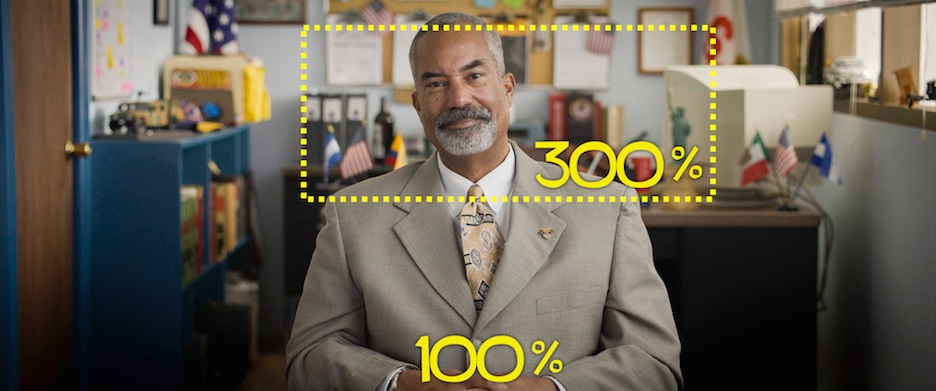

I’m shooting my documentary in 4K for the other reason: the Extraction Argument, which means: shoot 4K but finish in 2K. Doing that gives me a tremendous amount of latitude in post-production to zoom-in and re-frame my shots with no apparent loss of resolution in the final film.

Now let’s be clear: I am NOT a fan of re-framing shots in lieu of shooting coverage. By that I mean: shooting a medium shot and then blowing-up the shot in post to get the close-up rather than moving the camera and/or changing the lens for another take. When you’re shooting fiction and working with actors who are being paid to repeat their performances as many times as needed, I think you should move the camera, swap a lens and shoot a close-up. That will always look better.

However, nonfiction is very different. In a documentary, there is no Take 2. You can’t expect a non-actor / subject to give you a repeat “performance” for a close-up. So how do you cut your interview together? Well, you can shoot with 2 cameras – but that can add additional expense: it’s another camera package and another crew member. And even that doesn’t always work: in the case of my new doc, I want my interview subjects to be looking directly into the camera so there is no way to add a 2nd camera – you can only look into one camera at a time.

That leaves you with the option of jump-cutting your interview together and then covering the jump-cuts with other footage: b-roll, photos, archival, etc. This is a tried-and-true doc interview strategy and it’s exactly how we cut together “Bigger Stronger Faster”. But what if you want to stay in the moment? What if your subject is telling you something incredible and emotional? Cutting away to b-roll just to bridge a jump-cut can be so distracting when all your audience wants in that moment is to get CLOSER…that’s when 4K is an amazing solution.

For me, the Extraction Argument for shooting doc interviews has been by far the most compelling reason to shoot 4K. Much more compelling than shooting 4K for commercials or for SNL – both of which I have done quite a bit but nothing has made a bigger impact on the storytelling than when shooting 4K for a doc. As a way of editing together an emotionally engaging interview, I think this method is absolutely revolutionary.

On the post-production side, “Hobbit Office” and “Serial” were both cut in Adobe Premiere Pro. At SNL, our editor, Adam Epstein, is constantly bouncing between Premiere and After Effects – and to a lesser extent, Adobe Audition and Photoshop — so just using Dynamic Link alone saves us crucial time every week. Premiere’s ability to cut just about any format natively is another big reason we use it. You can even cut multiple formats within the same timeline, so for “Serial”, Adam could import the Arri Amira files, the 5DmIII footage and even the iPhone files into the same timeline, and just start cutting. The Amira shoots 2K ProRes – which is relatively lightweight compared to 4K RAW formats, so workflow was a breeze. But even when we shoot 4K RAW with the Epic Dragon, Adam has had no problem cutting the .R3D files natively within Premiere Pro.

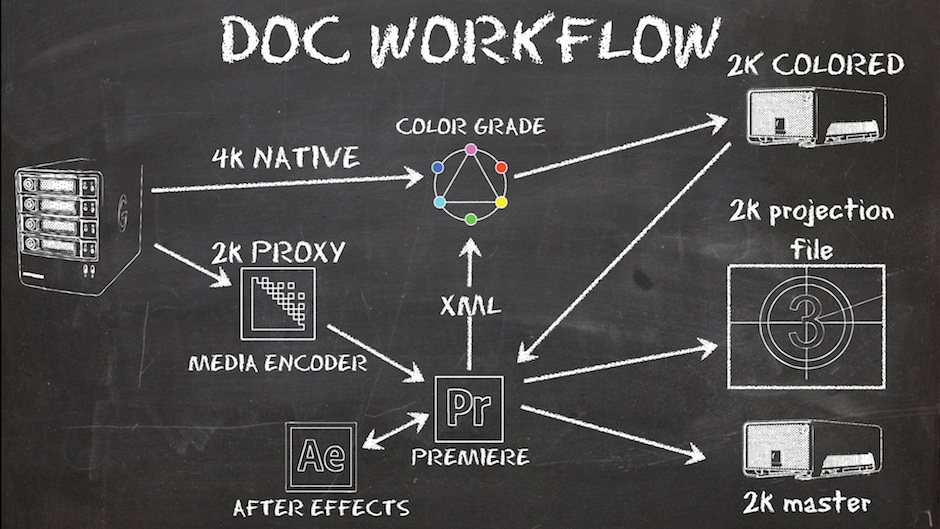

My doc workflow is a little different. I’m dealing with dramatically more footage than an SNL spot. At SNL we average about 2-3 hours of footage per shoot day. By comparison, for my documentary “Bigger Stronger Faster”, we shot over 300 hours of footage over the course of 2 years – and that was only HD resolution. For my new doc, the Canon C500 shoots uncompressed 4K at 1TB/hour! Imagine dealing with 300TB of footage…There is just no way I can afford THAT MUCH storage. So first of all, we’re definitely not shooting 300 hours of footage again. But we’re also using Adobe Media Encoder to create 2K Proxy files so that we’re not dealing with the massive 4K files until the very end of post. The proxy file are exact duplicates of the 4K footage but at 2K resolution and file size – the files names and timecode are all included in the duplicate. So we’re cutting the doc at 2K resolution and will later conform the 4K footage after we lock picture for the color grade. We’re also doing all of the re-framing in Premiere with the 2K footage, and when we export the XML file, it will even carry over all of the re-framing information for the 4K conform. value of my domain name day-trips The post workflow looks roughly like this:

I’ll be posting a couple BTS videos (HERE) along with more about the process on this documentary as we complete the film over the course of the next year. Hopefully this will be an interesting counterpoint to the “How We Did It” fast turn-around stories from the trenches of SNL.